Digging into an identity

things you learn about a loved one from what's inside a storage bin

I needed an empty storage bin.

Over the weekend, I rummaged through a closet to find one, only to see snuggly stored bins in various sizes filled with stuff—holiday decorations, an assortment of light bulbs of every wattage possible, candles, candle holders, my mother’s “good” Lenox china, wrapping paper . . . you get the idea.

The bin I was looking for was already filled with my late mother’s few remaining things: envelopes of photos faded to yellow, and some to gray, her birth certificate, diplomas, Holy Communion photo, social security card, a bible given to her upon her confirmation, a newspaper with the names (hers included) of the 1947 graduating class of St. Stanislaus Koska high school in Chicago, to name a few.

I pulled the bin off the shelf and hauled it into the living room. Set on the floor, I lifted the lid’s clasps; dust stirred, papers loosened.

I was familiar with her things, having moved them and her from our home to a condo to a senior living apartment. However, when I emptied the bin, I realized I had simply regarded them as personal keepsakes, believing they meant more to my mother than they did to me.

What one person may regard as keepsakes can, for others, be a way to discover things about them that were never known.

As I lifted each item from the container, I saw her in a way I never had before. I examined her things as markers of her life’s journey—her accomplishments, her successes, her relationships, and her memories of family and friends. I considered these items to be anchors for her memories, holding their places in preserved moments of her life.

I fingered through the vertical-standing items before pulling them out to make one pile. No time like the present to cull the container, especially since I needed it, anyway.

I sorted the pile into two—one pile would be thrown out, and the other I would keep, for just a little while longer.

Brown envelopes tore from old photos faded to yellow and some to gray that were stuffed into them. I fanned through the unrecognizable photos before tossing them into a garbage bag. I once recalled them as photos of her vacations as a single young woman. I had grown up knowing about Olga and Loretta, Alice and Phyllis, hearing stories, edited for mischief or private matters, no doubt, of their trips to the Bahamas, Bermuda and Cuba. But they were also photos that revealed how much she once loved the sun, the beach, traveling and exploring.

I settled on the floor and leaned against the couch. Small notebooks and notepapers slipped from the pile’s shape. There was an ivory hard-covered book, pocket-sized, with her name engraved in gold and “Birthdays” in raised letters. The copyright was in 1942.

The familiarity of this book made me set this one aside.

I had remembered this book. As a young girl, I often saw my mother refer to its pages. Birthdays, anniversaries, and deaths were noted on certain days of the month. Her copious notes guided her in sending cards in greetings and celebration, and in making phone calls, a personal connection with people on those special occasions.

I thought of how important acknowledging a friend or family member was to my mother; she wanted to make them feel truly special on their day.

And then there were three small pieces of paper.

My mother had handwritten a poem on each piece. One began, “When I am gone . . .” My tears mixed with laughter as I spoke to her. “You left these for me to read, didn’t you?”

I never thought my mother to be a reader of poetry, and yet she carefully copied a few favorites onto scraps of paper and kept them. Retracing the poetic words revealed a depth of emotion and connection I had never sensed.

Three pocket-sized notebooks remained on the floor.

A few diary-like entries were written in all caps, fitting tidily between the lined paper. One notebook reflected the weather for the day, and what she ate from the menu in the dining room. Another was her thoughts about “this sunny day” and who she met and chatted with downstairs. When I once understood her to prefer to stay to herself, how she loved to visit with friends on cheery days.

One notebook was unlike the others. Her words fell from the page as they became fewer, the lines shorter, the tone more desperate and perhaps fearful. She said she hurt and was in pain, listing her symptoms as if needing to recite them should she soon find herself in a doctor’s office or emergency room. I never knew how much she was really suffering in the weeks before entering the hospital until I read those pages.

I thought about how certain we can be that we have truly known someone until a time in the present shows us how much we never fully understood.

In Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, he suggests many selves are in each person and that we only encounter fragments.

“Each of us is really multiple,” he said. Only illusion of knowing may be what’s there, but time reveals how partial that knowledge always was.

I considered my mother’s note-taking a reflection of her many years as a secretary, keeping straight the importance of dates, people, and facts and her understanding of them. Perhaps the note-taking spilled over to copying her favorite poems so that one day I may read and enjoy them just as much as she did.

It took me four years after my mother’s death to see just how detail-oriented she was. She was a careful worker of words, sometimes printing them in all caps, not for emphasis, but simply because it was her way of being neat and clear with her written communication. And when admiring the poetry written by another, she’d trace the sentiments along with the emotion she and they carried, onto paper.

We may think our possessions have more meaning for the person who holds them than for us. But really, they hold lessons of understanding about a person we may never have really noticed.

We mistake familiarity for knowing until time—or loss—reveals how much of a person lived beyond our sight.

My mother intentionally saved these particular keepsakes because they were vessels of her identity.

I kept the “Birthdays” book. It is my keepsake to anchor memories of my mother, her family and friends of the past.

The bin was empty. But not before I visited my mother one last time in the places and times, when and where I would learn more about her and who she was, only after she was gone.

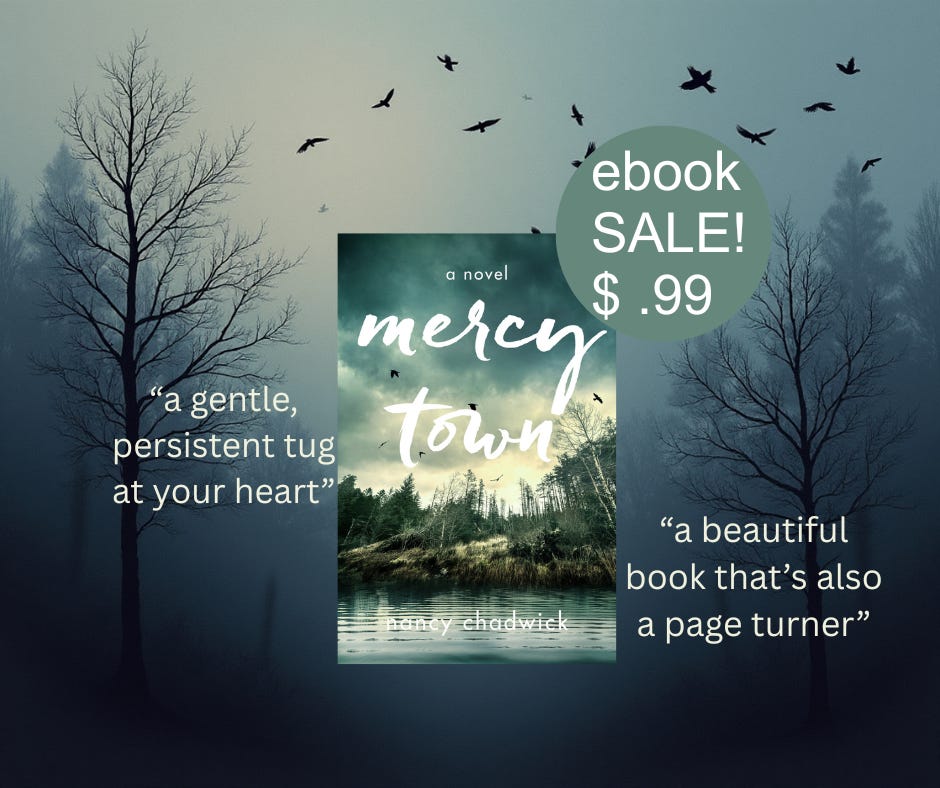

Mercy Town ebook is on sale!

Limited time only.

A sneak peek into Mercy Town:

I wasn’t the only one whose life changed forever the minute the echo of a loud bang sliced its way through the spines of the spruce and the arms of the tamarack. The resonance was preceded by a soft click that was the talk of neither mature red winged blackbirds nor young crows. Some people moved on from the aftershocks of that late afternoon spring day, and some didn’t. For those who didn’t, the hate grew over the years to a seeming point of no return. It defined them as something other than what I remembered them to be—kindhearted, forgiving. For others, they held their compassion inside, close to the heart, so as not to excite the ire of those who were opposed, sending the town of Waunasha into a frenzy of disunity that couldn’t be touched because of its heat. It just wasn’t right.

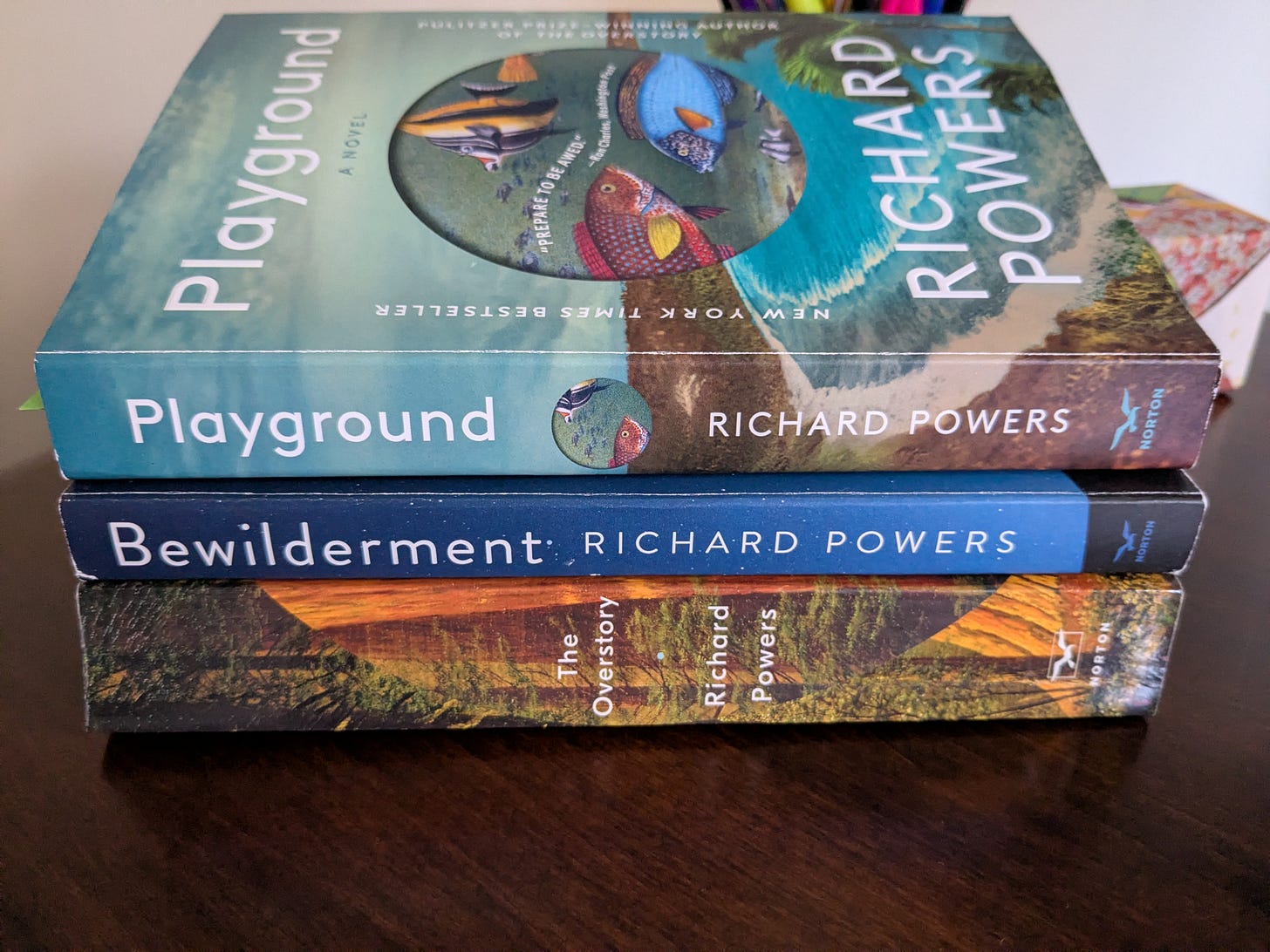

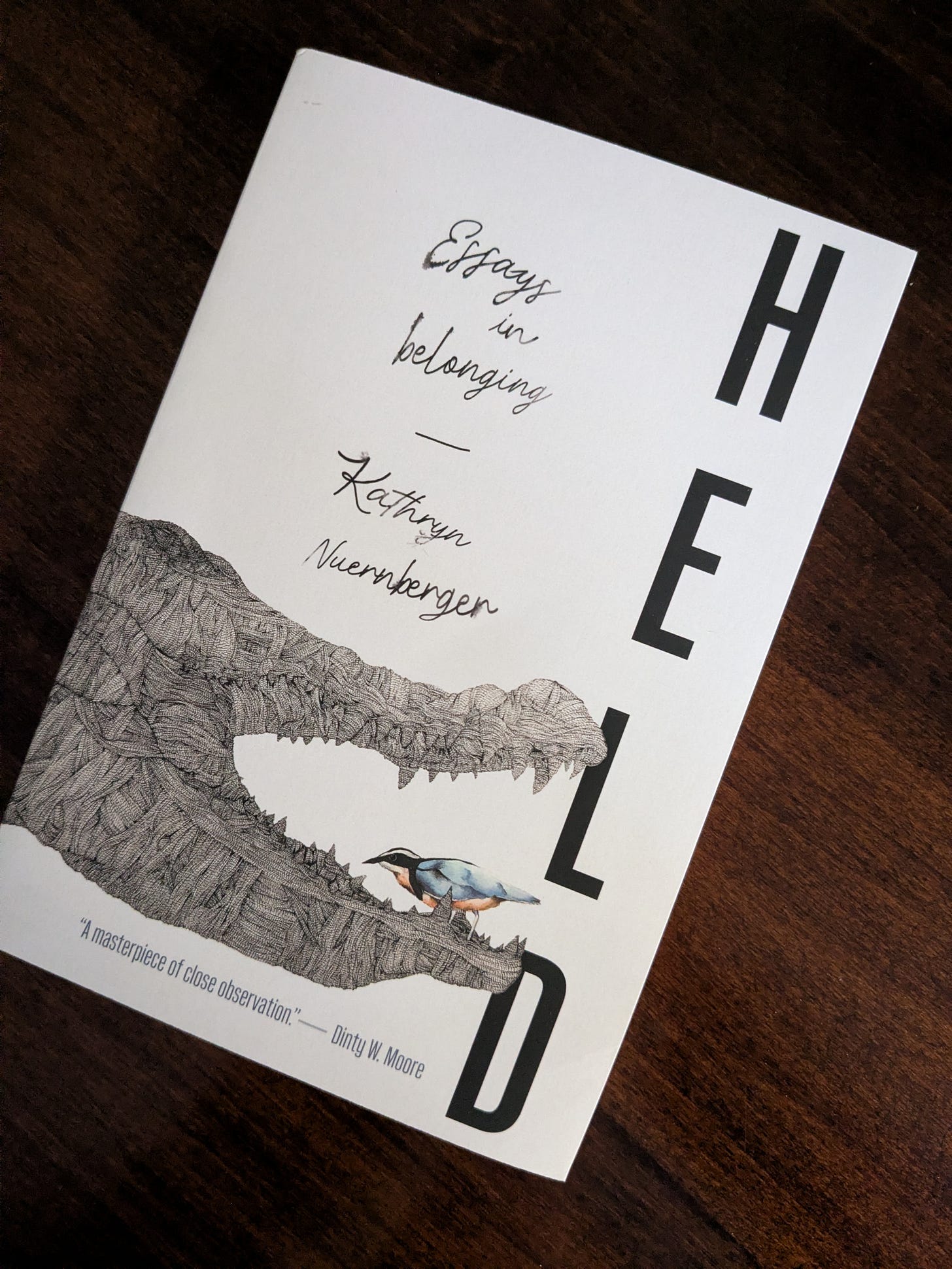

WHAT I’M READING

RICHARD POWERS - After devouring The Overstory years ago, I’m glad to learn there was more of him to read!

NEXT UP . . .

AND . . . What I’m sharing . . .

IN CLOSING . . .

I chose this poem because seeing winter, in its bareness and cold, forces us to see things as they truly are, rather than as we wish them to be.

The Snow Man by Wallace Stevens (first published in 1921)

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is

Lovely reflections... just went through a bunch of my parents' boxes.. so identify ...